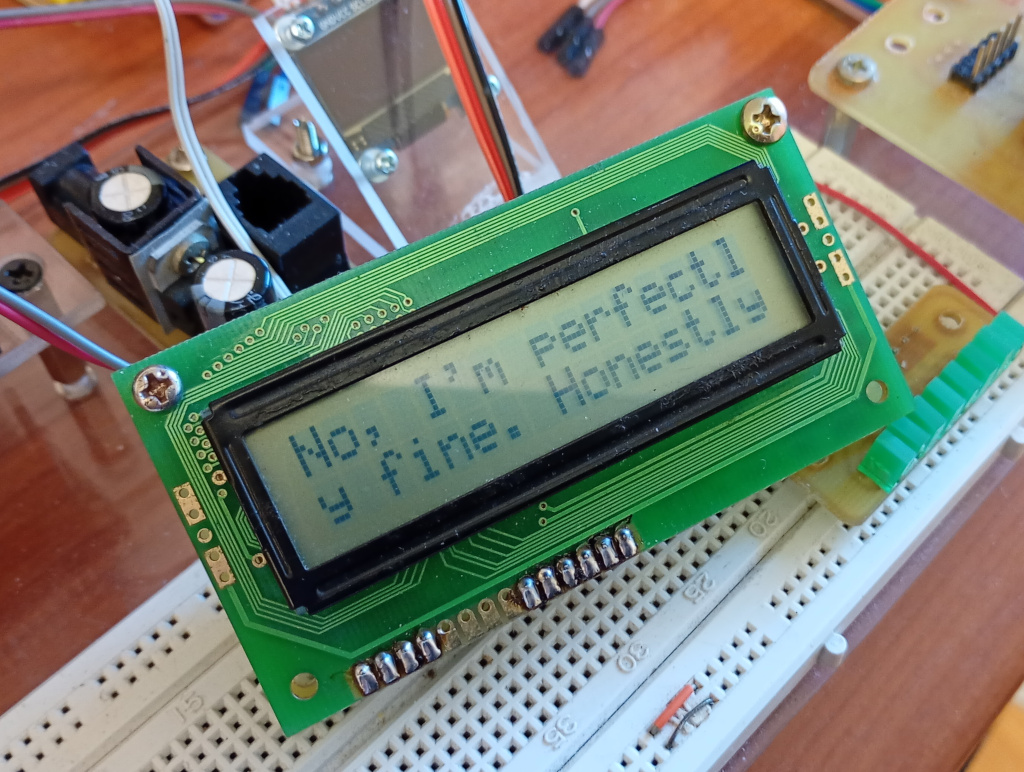

I achieved something today.

For a while there I wasn’t sure I would but it eventually came together.

Last night I soldered together one of my new LCD driver boards. I’ve had a few different driver boards, with designs going back to 2006, maybe earlier, but I recently sat down to redesign one of my boards. The old design had a lot of empty space, a consequence of having to leave space on the board for the LCD module and the remaining components like the PIC chip.

I took an existing design and flipped it over, so that the LCD module was mounted on the copper side, meaning that it wasn’t interfering with any of the components on the reverse side. That meant that I could shrink the design into a space only very slightly bigger than the size of the LCD module. It could have been a fair bit smaller, except that I wanted to project the mounting hole pattern of the LCD module onto my control board. So even though it’s much smaller, there’s still a lot of empty space on the board.

After building the board I needed a way of testing it. That’s where today came in. Well, actually I started last night but I didn’t get anywhere and deleted everything.

First I needed a PIC program. I had plenty of working code so I opened one of my old files and stripped out piles of useless code. Useless in the sense that I wanted the Pico to actually send the messages to the PIC rather than, as in the past, sending a message code that the PIC would display from a list of preprogrammed messages. I wrote what I thought was a working algorithm and burnt it to the PIC, eventually, the programming is really kinda flaky.

Then I needed to write a program for the Pico. This was tricky, because I wasn’t sure of the syntax for sending a binary representation of a hex stream, or how to send a null character, or anything really. So I copied the example UART code from the Pico Python SDK and no surprise that it didn’t work. I knew I needed to send a binary string and since the PIC was expecting bytes in hex format I thought maybe I could write a string of hex digits. so I tried sending a line like b’\x41\x42\n\r’ and nothing happened. Nothing kept on happening until all at once a screen full of Japanese letters appeared. I realised that this was because my PIC code had a buffer of 32 characters which once full would be written to the display. I then had to figure out what the codes were for the different characters. I tried different values and got a range of characters that didn’t seem to make much sense, but persisting I discovered that I could get the display to show different characters with lines like b’\x41\x41\n\x41\x42\n’ which still didn’t mean anything.

Well I tell a lie, because I discovered that the pairs of numbers were combining in an odd way that ended up being a representation of the character memory space of the LCD module. Looking at the datasheet for the module I eventually concluded that in the string b’\x41\x42′ the first hex code represented a column in the memory space and the second hex code represented a row. With this information I was able to identify the codes for each of the characters.

Except that all this was unnecessary.

At some point I began trying to work out a method of turning ordinary strings of letters into strings of binary hex characters. Using the hex() method resulted in hex codes in the format of 0xNN, but I wanted \xNN, because that’s what I thought was working. Well I tried a few things and couldn’t get it right because trying to replace 0x with \x wasn’t working, yes I know that’s probably noobish, bite me. Then I thought, what would happen if I just used a double backslash.

By this time I had changed my Pico program to forcibly fill the PIC’s 32 byte buffer, forcing a screen draw. I tried sending the line b’\\x35\\x32\\n’ and got a line of 5’s and 2’s. or something like that. That wasn’t what I was expecting. Up to this point the program was creating one character on screen from 2 hex characters, not sure if I’m explaining it, but using only one backslash in the string like b’\x35\x32\n’ resulted in a capital R for example. Suddenly, adding another backslash I was getting one character for one hex code. Looking at the code more carefully I realised that the hex code was actually the ASCII code for the character. I mean, that’s expected behaviour.

Once I got to this stage the job was practically done. I wrote a plain text ‘HELLO!’ message and iterated through it letter by letter, converting them into hex codes. By now I had already discovered that I could force the LCD to display a message by adding a ‘\\x00’ for the null character. I ran the code and it said ‘HE !’. I got the program to print out the string being sent and noticed that the non printing letters had hex codes with letters in them. Clearly capitalisation was important, so I added an upper() method to change the hex codes to all uppercase. Fortunately the code didn’t care whether the x was capitalised, or even that it was there at all.

At this stage the code was working well enough for me to start thinking about how to get the LCD to print on the second line. In a long message this was handled automatically but for manual control I sacrificed the tilde to be the ‘go to line 2’ flag. While I was typing this I thought, why not use \r? Well I tried it and it seemed to work okay but then I was getting strange errors. The messages were getting all messed up. I’ve realised that’s not a problem of the character being used, but because the PIC is automatically counting characters to know when to swap to line 2, but if I manually command the LCD to print on line 2, the letter count isn’t reset, so even though the message might already be printing on line 2, as soon as 16 characters are received it returns to the start of line 2, messing up the display. You know what, its, easy enough to fix.

So there we are then. I’ve managed to get the Pico talking to my ancient LCD modules with an unholy alliance of PIC BASIC and MicroPython and probably chewing gum.